The ThursgivingDay Report – Issue 316

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Thursday, November 18, 2021Issue 316

Pixabay Licensed: Free for commercial use, No attribution required. From the Law Offices of Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A. Having trouble viewing this? Use this link

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

~ ON THIS DAY ~Happy Birthday To The Lead Guitarist Of Metallica – Kirk HammettIn 2003, Hammett was ranked 11th on Rolling Stone‘s list of The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.

This image was originally posted to Flickr by Raph_PH on Wikimedia Commons; a collection of freely usable media files to which anyone can contribute. Fun Facts about Kirk Hammett. Learn More about the Clash of the Titans: The Beatles’ White Album vs. Metallica’s Black Album. Click HERE to listen to a list of Metallica’s top songs featured on the Rolling Stone Album Guide.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table of ContentsArticle 1Planning for the Affluent Charitable ClientAs published by Bloomberg BNA Tax Management Estates, Gifts, and Trusts Journal 11/10/2021. Written by: Alan Gassman, Wesley Dickson, Ian Maclean, and John Beck Article 2Excerpts From Nov. 16th St. Petersburg/Clearwater Estate Tax Planning Panel DiscussionA Q&A Between Alan Gassman and Hamden Baskin Article 3Part II and Part III: Reducing Estate and Trust Litigation Through Disclosure, In Terrorem Clauses, Mediation, Arbitration and Pre-Mortem ProbateWritten by: Jonathan Blattmachr For Finkel’s FollowersHow To Stop Doing Everything YourselfWritten by: David Finkel Forbes’ CornerWhat Estate Planning Should You Do Now That Congress Might Not Change Anything?Written by: Martin Shenkman Featured EventAll Upcoming EventsYouTube LibraryHumor

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Article 1Planning for the Affluent Charitable Client

Written by: Alan Gassman, Wesley Dickson, Ian Maclean (not pictured), and John Beck Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A. & Colen and Wagoner, P.A. Reproduced with permission from Tax Management Estates, Gifts, and Trusts Journal, 46 EGTJ 06, 11/10/2021. Copyright R 2021 by The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (800-372-1033) http://www.bna.com. Alan S. Gassman, J.D., LL.M., is a Board Certified Wills, Trusts, and Estates lawyer and a partner in the law firm of Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A., and practices in Clearwater, Florida. He is co-author of Gassman and Markham on Florida and Federal Creditor Protection and several other books. Wesley J. Dickson, J.D., graduated from Stetson University College of Law in 2020 and works as a legal assistant at Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A. while he is awaiting his bar results. Ian MacLean, Esq., (not pictured) is a recent graduate of Stetson University of College of Law, where he received his Certificate of Concentration in Elder Law. Prior to attending Stetson University College of Law, Ian received his B.A. in Political Science from Stetson University. Ian is a licensed attorney in the state of Florida. John Beck, J.D., MBA, L.L.M. is an attorney in Largo, Florida where he practices in the areas of estate and trust planning, taxation, and corporate and business law. John is the author of several published tax and estate planning articles and a frequent national webinar presenter. INTRODUCTION Many wealthy Americans leave their assets to charity on death without having made the most efficient and effective use of charitable income and gift tax deductions. Further, many have failed to take advantage of opportunities to guide and participate in charitable causes during their lifetimes. In addition, many families could have derived greater charitable and non-charitable benefits if more thoughtful planning had taken place. This article will describe a number of planning opportunities that are commonly overlooked, misunderstood, or simply not known to be available. The subject of taxation of charitable arrangements is both complicated and commonly confusing or ill-defined. There is a shortage of good books and treatises due to the complexity of the rules and the relatively small portion of the population of tax professionals that have invested the hundreds of hours that are required to have a solid grasp of many of the principles involved. Competent and conscientious tax professionals will be wise to confer with sub-specialists who may have information and experience on planning and arrangements which are not well known or understood by mainstream advisors, or covered by literature or outlines that are available from mainstream conferences. LEAVING IRA AND PENSION BENEFITS TO CHARITY Often, wealthy individuals die leaving charitable devises under a revocable trust or last will and testament while devising their IRAs for the benefit of friends and family. The opposite should be the case. Leaving $1 million in a traditional IRA for descendants and $1 million of other assets to charity causes the descendants to pay income tax at ordinary income tax rates on the total value of the IRA. Charities, on the other hand, pay no tax on monies or assets in kind received from an IRA or pension made payable to them. Individuals can also avoid paying income tax on Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from their IRAs and pension plans by making Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs). Signed into law on December 20, 2019, the ‘‘Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement Act of 2019’’ (the SECURE Act) made significant changes to the tax law regarding distributions from 401(k)s, IRAs, Roth IRAs, defined contribution plans, and other types of pension plans or qualified retirement accounts. A provision of the SECURE Act changed the age at which individuals are required to begin making RMDs from the IRA or pension plan. Specifically, the SECURE Act provided that individuals who reached the age of 70 1/2 in 2019 were required to distribute the first RMD by April 1, 2020, to avoid penalties. Individuals who had not yet reached age 70 1/2 by the end of 2019 were not required to take an RMD until April 1st of the year following the year in which they reached the age of 72. Notwithstanding the age requirements for RMDs provided above, an individual who has reached the age of 70 1/2 can cause distributions of up to $100,000 a year to pass directly to charity by making a Qualified Charitable Distribution, giving such individual the equivalent of a 100% charitable deduction. Section 408(d)(8) provides that the distribution must be made directly by the trustee of the IRA (other than a SEP or SIMPLE IRA). Additionally, to claim a deduction for the charitable contribution, the individual must obtain an acknowledgment of the contribution. There are seven requirements that an IRA distribution must meet to qualify as a QCD: 1. The donor must be at least 70 1/2; 2. Distribution must be from an IRA; 3. The distribution must go directly to the charity from the IRA; 4. The recipient must be an (a) Public Charity, (b) Private Operating Foundation, or possibly (c) a Conduit Private Foundation; 5. The payment would otherwise be fully qualified as a charitable income tax deduction; 6. The distribution would otherwise be taxable, with a maximum amount of $100,000 per year; and 7. The donor must have documentation that the charity would typically qualify for a full charitable income tax deduction. Married couples who file joint tax returns may each make a $100,000 QCD, so long as they have both attained the age of 70 1/2. A QCD that exceeds the $100,000 exclusion limit is included in income, and if the IRA includes nondeductible contributions, the distribution is first considered to be paid out of otherwise taxable income. LEAVE INCOME INSTEAD OF PRINCIPAL UPON DEATH There is a big difference between providing that ‘‘$100,000 will be payable to my church, with the remainder to my children,’’ and providing that ‘‘the trust assets will be held so that the first $100,000 of income will be payable to my church, with the remaining assets going to my children.’’ Using the latter example causes income that would otherwise be taxable to the children, whether during the administration of the estate or trust or thereafter, to instead be carried out to the church, which can receive it tax-free. To prevent complex trusts from having business or debt-financed income offset by the §642(c) deduction, §681(a) limits the deductions that will apply under §642(c). Section 681(a) defines ‘‘unrelated business income’’ of a trust to mean the amount that would be computed to be its ‘‘unrelated business taxable income’’ under §512 if the trust was a 501(c)(3) organization. This, therefore, causes business income, including rent that is based upon the profits of a tenant and rent of personal property that is more than incidental to the leasing of real estate along with the sale of property by a trust that is a ‘‘dealer’’ to be offset only in a limited manner by distributions that the complex trust makes to charity by reason of the deduction permitted to charitable organizations who have UBTI and distribute it to other charitable organizations applying to a complex trust. Further, Reg. §1.681(a)-2 permits a trust agreement to specify the source of charitable contributions in order to avoid a pro-rata allocation. For example, if a complex trust has $10,000 of tax-exempt municipal bond income, $40,000 of income from an active business not related to charitable purposes, and $50,000 of rental income that is determined without relation to the net income of the tenant, then a $50,000 transfer to a 501(c) charity would be deductible at most based upon 50% of the transfer if the trust agreement does not specify how income is allocated for a contribution. Alternatively, if the trust document specifies that distributions to charities shall be made first from income that would not be considered to be “unrelated business income” under §681(a) or tax-free income under §103, then the full $50,000 tax deduction would be available (instead of a $25,000 tax deduction). The Funding of Private Foundations, Private Operating Foundations, Donor Advised Funds, and Community Foundation Accounts While Living [S2] [UC] Many affluent Americans earmark significant assets for charity, but do not give them away during their lifetimes because they want to retain control, have not decided exactly how they want to the assets to pass or believe that they may be needed for support if there is an international financial disaster. Such clients may feel comfortable funding a private foundation or private operating foundation that compensates them and/or members of their family for services rendered if ever needed, and which can be controlled by the client for the client’s remaining lifetime. The foundation’s uses and objectives can change over time. Private foundations and Private Operating Foundations are relatively easy and inexpensive to form, and do not have to be time-consuming or cumbersome to maintain if properly managed and organized. A tax deduction can be received for the contribution of appreciated assets that would otherwise be subject to capital gains tax upon sale, including closely-held stock if certain requirements are met. Donations to Private Operating Foundations generally have the same tax treatment as donations to public charities, provided that certain rules must be met to assure that the unrelated business taxable income, disqualified person, excess business holdings, self-dealing, and other rules will not be violated. For example, property subject to a mortgage may be gifted to a public charity to receive an income tax deduction based on the excess of the fair market value of the property over the mortgage, but this can be done with a Private Operating Foundation or a Private Non-Operating Foundation only if certain requirements are met. Rent income that is received by the private operating foundation from the rental of leveraged property will be subject to the unrelated business taxable income rules unless an exception applies, such as if the debt was on the property at least five years before the donation occurs and is paid in full within 10 years after the donation is made. While it would appear at first look that the estate and the revocable trust of a decedent that was a disqualified person during their lifetime could not typically transfer leveraged property to a private foundation or private operating foundation, there is support for the proposition that an estate is not a disqualified person until it has become a substantial contributor. An estate will generally not be a disqualified person at the time of the first transfer from the estate to the charity under what is known as the “First Bite Rule.” This exception does not exist for donors who are living, and appears to have been created by the IRS as an exception to the general rule. GCM 39445 (I.R.S. Nov. 12, 1985) indicates that an estate is not a disqualified person within the meaning of §4946 merely because the decedent was a disqualified person, and that an estate is only a disqualified person if it qualifies on its own regard (i.e. becomes a substantial contributor). This is an interpretation of the First Bite Rule”. The Administrative Note Exception Reg. §53.4941(d)–1(b)(3) provides an exception to the self-dealing rules that can be of significant value to estates that leave assets to Private Foundations and Private Operating Foundations. Under this exception, the self-dealing rules will not apply where a “Disqualified Person” is entitled under an option agreement meeting certain requirements to purchase assets from an estate or the revocable trust of a decedent that would otherwise pass to a §501(c)(3) charity. In other words, on the death of a person who leaves assets to charity, the tax law may permit the family or other trusts left by that person to buy assets from the estate or revocable trust for a note that is owed to charity after the person’s death. This can be a useful tool in providing family members with the option to purchase business interests that would otherwise go to charity upon a decedent’s death, subject to a number of requirements listed in the above-mentioned regulations. If an option is in place, this strategy could be a way to limit risk to individual beneficiaries. For example, if you provided an individual beneficiary with an option to buy interest in a high-risk business that would otherwise go to charity. This would allow the individual to assess the value and risk associated with that business interest after the decedent’s death and determine whether to purchase such interest. This is especially valuable for those who want to benefit charity but are more concerned that their family members or other beneficiaries are adequately supported. It is worth noting that the applicable rules and regulations permit a 25-year interest-only note, which can be at the long-term applicable federal rate, but that the note cannot be renegotiated as long as it is owed to a Private Operating Foundation if the holder of the note is a disqualified person in relation to the Private Operating Foundation. Once the Private Operating Foundation is converted to a Public Charity, the note can most likely be renegotiated. Generally, Public Charities are controlled by a board with a majority of individuals that are unrelated and disinterested. If the Public Charity is controlled by related individuals that would be disqualified if the Public Charity was instead a Private Operating Foundation, then a tax professional should be consulted before renegotiating the note. When Leaving It All to Charity on Death [S2] [UC] Make Use of the Client’s Unified Credit Amount to Assure Maximum Flexibility [S2] [UC/LC] It is worth noting that an irrevocable trust may be established for charitable purposes without qualifying for the estate tax charitable deduction if the deduction is not needed because the descendant has unused credit exemption amount. Such a trust can be held to benefit 501(c)(3) charities, which can include the descendant’s private operating foundation or preferred public charity, while also providing benefits for individuals, animals, then environment, or other purposes which do not qualify as 501(c)(3) charities. By including charitable entities that are not considered 501(c)(3) charities, the trust can avoid being subject to the restrictive private foundation rules. If a trust only benefits 501(c)(3) charities then it would be considered a private foundation and be subject to all of the private foundation rules. These limitations, which could be avoided using the above strategy, would allow the trust to maintain ownership and control over non-charitable business activities, hold S corporation stock while not being subject to the unrelated business taxable income rules (which would make the sale of the stock taxable without an offsetting deduction), and to avoid reporting its activities to the general public on a Form 990, Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax, income tax return or pay the 1.39% excise tax on net income that private foundations and Private Operating Foundations are liable for. In addition, an individual who serves as trustee of such a trust may feel less exposed to liability, and may enter into arm’s-length agreements and transactions that are not permitted with respect to public charities or Private Operating Foundations, with the end result being greater good for charitable causes and less tax liability. Planning with Multiple Owner Flow-Through Entities to be Left On Death: Partnerships of S Corporations are Often Preferred Suppose that a taxpayer has several restaurants owned two-thirds (2/3rds) by S corporations owned by the client and one-third (1/3rd) owned by an S corporation owned by his partner. All S corporation income is subject to the Unrelated Business Income Tax and too much of such K-1 income may cause disqualification from 501(c)(3) status. The S corporations can be converted to C corporation status before two-thirds (2/3rds) ownership is gifted or left on death to charity, but the one-third (1/3rd) shareholder does not want this to happen because it will cost him more if this occurs. This is much less flexible than when a restaurant is owned by an S corporation owned two-thirds (2/3rds) by the Taxpayer and one-third (1/3rd) by his or her partner, because the one third (1/3rd) partner will typically not want to convert the entity to C corporation status. Understanding The 35% Beneficial Interest Exception Under Section 4946(a)(1)(G) [S2] [UC] Under §4946(a)(1)(G) voting stock held by the trustee of a trust that provides that no more than 35% of its beneficial interests will be held for any person or persons related to the trustee will not be considered to be held by a Disqualified Person if certain requirements are met. Therefore, a family wishing to control an entity partly owned by charity can place all of the voting stock or interests in the investment or business entity under a trust that may provide up to 35% of its holdings as benefits for family members or others, with 65% of the holdings of the trust to benefit charitable or quasi-charitable organizations. In order to prevent such a “voting stock trust” from being treated as a separate charitable organization, which would cause the trust itself to be treated as a Private Foundation, ideally all, or at least some of, the beneficiaries should be individuals or organizations that are not considered to be charities as defined in §170(c)(2)(B). This can include close friends or employees who are not related by a familial relationship to the donor under §267(b), §501(c)(4) social wealth organizations and cemetery associations or other non-charitable entities that the grantor of the trust may wish to benefit. It is noteworthy that S corporation stock may be held under a trust that benefits individuals and 501(c)(3) charities. Maintaining Confidentiality When Giving to Charity Clients who wish to remain confidential in their giving can consider the following strategies: 1. Form a limited liability company owned by the client but having its own separate name and taxpayer identification number. That LLC can be the donor instead of the client, and the LLC will therefore be listed on charitable organization rosters and disclosure forms instead of the name of the client. IRS rules preclude disclosure of the owner of an entity, and if the LLC is formed and maintained in a state that does not require or disclose ownership then confidentiality can be maintained. For example, Wyoming does not even require disclosure to the State of Wyoming of the manager or managers of a Wyoming LLC, or its owners. 2. To make it less likely that anyone will obtain information with respect to details or operations of a 501(c)(3) organization, put as much information as possible in exhibits to the Form 990. Presently, the IRS discloses the Form 990, but not the exhibits to the Form 990. The authors have noticed many Form 990s where almost all the information about the entity has been provided in the exhibits, because it is difficult and time-consuming to request and receive the exhibits. Receiving a Charitable Deduction for the Contribution of a Remainder Interest in a Personal Residence or Farm Section 170(f)(3)(B) provides that a charitable deduction is allowed for a contribution, not in trust, of a remainder interest in a donor’s personal residence or farm. The donor is entitled to a charitable contribution income tax deduction equal to the present value of the charitable remainder interest. The calculation is made using the guidelines described in Reg. §1.170A-12 and is based on the following:

A charitable contribution of an encumbered personal residence or farm is prohibited by neither the Code nor the Treasury regulations. In PLR 9329017, a donor purchased a farm for $110,000, which he financed by paying $30,000 in cash and obtaining a mortgage for $80,000 from a financial institution. The donor proposed to donate a remainder interest in the farm to charity while still remaining liable for payment of the mortgage. The IRS ruled that because the property would be transferred subject to a mortgage, the transfer would be considered a bargain sale between the donor and the charity. The IRS stated that the donor would be allowed a charitable deduction for the remainder interest of $30,000, and any subsequent payment of the principal of the mortgage by the donor would be regarded as an additional donation of a remainder interest in real property to the charity with the contribution being measured by the value of the remainder interest in each payment of principal. The IRS additionally ruled that, upon the transfer of the remainder interest in a donor’s farm to charity, the donor would realize the entire amount of the indebtedness for purposes of determining gain under the bargain sale rules, not just the debt attributable to the remainder. Leave the Estate Tax Exemption Amount to a “Non-Charitable Trust” on Death Charitable individuals who plan to leave “almost everything to charity” should consider leaving their estate tax exemption amount (the amount that can pass estate tax-free) to a trust that can be established for charitable purposes without qualifying under §501(c)(3) or any other §501(c) category so as not to be subject to the various limitations and prohibitions that apply to not-for-profit entities. That trust may register as an Electing Small Business Trust (ESBT)_and own S corporation interests and use the profits from the interests to help the same individuals and/or causes that the 501(c)(3) organization would support, and also provide support for individuals who could not be helped by the 501(c)(3), such as individuals who are ascertainable. A trust will qualify as an ESBT if: 1. All trust beneficiaries would be eligible shareholders if the stock was directly held; 2. No beneficiary paid for their interest in the ESBT; and 3. The trust files a Form 2553, Election by a Small Business Corporation election with the IRS. In the example of the restauranteur above, the Taxpayer may like to see educational and retirement benefits given to ex-employees of the restaurant, and their families, after his death. This cannot easily or safely occur under the 501(c)(3) organization but could occur under the non-section 501(c)(3) Trust, in addition to giving bonus compensation to key employees above and beyond what might be “reasonable and necessary” under the entities that will be owned for the 501(c)(3) organization. When S corporation stock is held by an individual or his or her revocable trust and will pass to a Charitable Lead Trust or Charitable Remainder Trust upon death, the estate or revocable trust will have two (2) years from the date of death to liquidate the stock. A Qualified Subchapter S Trust (QSST), which is similar to a grantor trust can hold S corporation stock where the remainder interest is going to charity. This type of planning will work well for a Qualified Terminable Interest Property Trust (QTIP). A QTIP allows a taxpayer to gift assets to his or her spouse during the taxpayer’s lifetime. However, unlike a traditional grantor trust, the grantor in a QTIP retains control of the property, even after his or her death. Dispositions to Charity under a McCord/Petter-Type Family Installment Sale [S2] [UC] In the Tax Court cases of McCord v. Commissioner and Petter v. Commissioner, taxpayers sold privately owned investment or corporate interest to trusts for descendants in exchange for notes based upon sale agreements that included adjustment clauses to provide that any value in excess of the agreed sales price pass at the time of the sale to a 501(c)(3) Public Charity in a manner intended to qualify for the federal gift tax charitable deduction. At the same time, the transactional documents provided for a small portion of the business entity to pass to the 501(c)(3) charity, and the 501(c)(3) reviewed and participated in the negotiation of the documents and also reviewed the valuation reports, presumably exercising appropriate fiduciary duties to assure that the organization was properly represented. One apparent reason for use of the charitable overflow arrangement was to overcome the IRS argument that adjustment clauses are contrary to public policy because they prevent the IRS from recharacterizing value. The opinions in McCord and Petter specifically found that it would not violate public policy to have an adjustment clause where the excess value determined to exist for gift tax purposes would go to charity. Under the McCord and Petter arrangements a small sliver of the applicable family entity was treated as going to charity at the moment of sale, and the only open question was whether a larger percentage of the entity was transferred to the charity at the time of the sale. In other words, as opposed to the agreements indicating that the charity was receiving a percentage of the company and would therefore receive a greater percentage later if determined appropriate by a tax court or other court of competent jurisdiction, the agreement indicated that the charity was receiving a percentage of the applicable entity equal to a portion sufficient so that there would be no gift being considered as being made to the family trust that was purchasing the rest of the applicable percentage for a fixed dollar amount. For instance, if the sales price was $1 million for 25% and the charity was receiving 1% at the time of the transfer, if the Tax Court found that 25% of the entity was really worth $2 million then the charity would be receiving 13.5% at the moment of the transaction, and the parties would correct percentages of ownership and provide makeup payments to take into account that the charity actually received 13.5% instead of 1% at the time of the sale. Fluency Test for Tax Advisors who have Clients with Real Estate Prior to engaging in charitable planning for clients with real estate, it is imperative that tax advisors ensure they are fluent with respect to the following items: 1. What kinds of appreciated real estate will qualify for fair market value tax deduction upon donation. 2. That this will apply to contributions to both Public Charities and Private Operating Foundations. 3. Most forms of rent income can be received tax-free by a charity, or by a charity owning partnership interests in a “Landlord Partnership,” but not in S corporations. 4. A client who has donated a real estate, business or investment interest to a Private Operating Foundation or Public Charity can retain control while receiving a tax deduction. 5. A client entering into an installment sale to a family entity will be safer from gift tax reclassification if there is a formula adjustment clause causing the overflow going to a charity so that the adjustment clause is not against public policy. 6. S corporation stock can be transferred to a 501(c)(3) organization, but all K-1 income will be taxable – not just unrelated business taxable income. 7. An S corporation cannot be owned by a charitable remainder trust or a non-grantor CLAT. 8. Partnership K-1 income received by a charitable remainder unitrust is taxed as a 100% excise tax. 9. A Flip NIMCRUT can defer the tax from the sale of a major asset for up to twenty years with relatively minimal amounts passing to charity. 10. Public charity status can be reached by operating a school, medical facility, medical research organization, or house of worship. 11. Upon death estate tax can be avoided by having family members buy assets that can pass to a family-controlled charity in exchange for an “administrative note” whereby the family members receive the investment assets and/or business and pay the family charity on a low-interest long-term note. This note may be negotiated down once the family charity becomes a “public charity” by operating a school, medical clinic, medical research organization, or house of worship. 12. The estate tax is also absolutely voluntary for those who would gift or leave assets to a charitable lead annuity trust that is zeroed out for estate tax purposes. This article may be cited as Alan Gassman, Wesley Dickson, Ian McClean, and John Beck, Planning for the Affluent Charitable Client, 46 Est., Gifts & Trsts. J. No. 6 (Nov. 11, 2021). All section references herein are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”), or the Treasury regulations promulgated thereunder, unless otherwise indicated. Credit to Christopher R. Hoyt, Transferring Deferred Comp to a Charity, 47th Annual Notre Dame Tax & Estate Planning Institute (2021). The authors would like to thank Karl Mill of Mill Law Center for the significant assistance he provided during the drafting of this article. LISI Charitable Planning Newsletter #280 (March 11, 2019) at http://www.leimbergservices.com Copyright 2019 Leimberg Information Services, Inc. (LISI) Reproduction in Any Form or Forwarding to Any Person Prohibited Without Express Written Permission.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Article 2Excerpts From Nov. 16th St. Petersburg/Clearwater Estate Tax Planning Panel Discussion

By: Alan Gassman and Hamden H. Baskin III Hamden Baskin: Talk to us about the current tax. What will the exemption be next year? Are there no barring changes? Tell us what may be out there for changes that you may be able to talk to us about briefly. Alan Gassman: Sure. So right now the estate tax exemption is $11,700,000 per person. So mom and dad can pass 23.4 million out to their descendants with very little planning. There is a portability allowance. So if the first dying spouse does not use the entire 11,700,000, the surviving spouse can have use of that. If the first dying spouse files an estate tax return and makes the portability election. So when you are representing people with children by separate marriages, make sure that there is an agreement that the surviving spouse or the personal representative will file that portability allowance, because it’s worth a lot of money to the surviving spouse. And it is really mean if you do not do that. Now, the annual gift allowance is $15,000 a year this year. So I could give $15,000 to everyone I know and love all three of them and not have to include that on any sort of return. The $11,700,000 goes up with what they call chained inflation, which means a little bit slower than inflation. It will be 12.06 million in January. And the $15,000 is also adjusted for inflation about every three or four years. It clicks forward in increments of a thousand. It will be $16,000 next year, up from $15,000 on September 25th of this year. The House Ways and Means Committee, which is where all tax bills start, really put a scare into a lot of affluent Americans by proposing a bill. It was only 910 pages long, but it would have reduced the $11,700,000 exemption to one-half of that. It would have reduced the gift tax exemption to one-half of that. And it would have been effective January 1st of next year. It would have also cut the legs out from under the techniques that we know and love the greatest, which are irrevocable trusts, where the client, the taxpayer, has been considered to be the owner of the trust. So the client pays the income tax on behalf of the trust. So it can grow that much faster. So after that happened, and after many of us thought that there would be 50 senators voting for this to go forward, there was a tremendous effort by thousands of taxpayers and many now tired advisers to set up these irrevocable trusts and get assets into them. And then Senator cinema being very movie-oriented, apparently put the skids on and said she was not going to vote for any of this. So it is all on ice and it may never happen, but it sure was fun while it was happening. Hamden Baskin: Good. So just to make sure we understand for, let us say attorneys that do not have perhaps the really high wealth folks coming in north of 20 million, and let us say it is a sweet spot two to $5 million estate. You would still on the first step, go ahead and file a protective 706 and just tell them it’s worth the money because it does not cost that much. And look what might happen. Alan Gassman: Right. Because that surviving spouse could have a $6 million exemption. And remember the rule of 72, because we all forget this, your client comes in with a $4 million Merrill Lynch account. In 10 years, it is going to be an $8 million Merrill Lynch account. And in 20 years it is going to be a $16 million Merrill Lynch account by the law of averages. So they do not worry about it until it is too late sometimes. Hamden Baskin: I have some familiarity, but not much with a Spousal Limited Access Trust. I think this is something that we probably ought to at least know what it is and how it’s employed a little bit. Can you talk to us a little bit about that? Alan Gassman: This has become the darling instruments of the industry. So I could establish an irrevocable trust for my wife, Marcia. I can appoint my wife as the trustee. I could give that trust a gift of $2 million worth of my accounts. And then it is never subject to estate tax in my estate. And as long as my wife’s access is limited to what she needs for health, education, maintenance and support, it is never included in her estate. It is never subject to the claims of my creditors because I’m not a beneficiary of it. It is never subject to the claims of her creditors except for exception creditors because she is limited to what she can get out of it. She can have a power of appointment to direct where it goes when she dies. And if we are situated in one of the asset protection jurisdictions, I might be added back as a beneficiary if I ever had hard times. So in many ways, married couples prefer to have a significant amount of their assets in a SLAT, a Spousal Limited Access Trust, whether they need it for tax reasons or not, because of the creditor protection reason. And then later on, if there is a divorce, the trust stays for the children. So it can be a very important planning technique. Hamden Baskin: Now it says it is generally for the higher wealth folks or can you employ it in more modest estates? Alan Gassman: You do employ more modest estates because the continuity of the asset, the creditor protection feature, is very important to a lot of clients. So more often it is used for people who want to use part of their 11,700,000 exemption, but I think it is a candidate for anyone. Another candidate for many modest clients is the Florida Community Property Trust. It became effective this summer. Florida was the fourth or fifth state where you can have any Floridian or a Florida trust company as a trustee and a married couple can put their assets into the Community Property Trust. The purpose of the legislation is so that if one spouse dies, all of the assets of the trust receive a fair market value basis. They could be sold thereafter with no capital gains tax. So even a modest couple, maybe they have 500,000 worth of stock that they paid a hundred thousand for when dad dies and they want to sell that stock to put mom in a nursing home. Well, do you think they want to pay a 10% capital gain or a 20% capital gains tax? No. So in this Community Property Trust, you could report a full Step-Up on the first death. The other thing I really like about the Florida Community Property Trust is that no one can be a beneficiary of the trust from the married couple. It is not good for the children and their great-nieces and nephews and their housekeeper. Once it goes in that Community Property Trust, it is for the couple and the couple only. They can revoke it based upon the terms thereof, but I’m finding it to be a good instrument to protect a married couple’s wealth from taxes and from other threats to wealth. Hamden Baskin: That is a good one. You mentioned the basis issue. That is another hot issue that we have all been hearing about the potential loss for the full Step-Up in Basis and some of the rules they were going to employ. What is the word on the Step-Up Basis and date of death and how are you handling it? Alan Gassman: Well like anything else when you almost get it taken away, you appreciate it that much more. I personally think that the Step-Up in Basis is going to be there for the next 20 to 30 years. It is going to be very difficult to get an act to enact legislation that would take the Step-Up away. But I think what we need to remember as planners is that if you set up a joint trust between a married couple and if you set it up as a normal joint trust, there will only be a half Step-Up on the first death. If you set it up as a Joint Exempt Step-Up Trust, which is called a JEST you can get a full step-up on the first death. If you set up a joint trust and you think it’s a Tendency by the Entireties trust, you better check that document five times because the bankruptcy judges do not think that you can have a Tenancy by the Entireties joint trust. So when a client comes to you for a joint trust, it is not just any trust. Is it a TBE trust? Is it a non-TBE trust? Is it a JEST trust? I think because that Step-Up Basis is important. The other thing we can do using the Optimal Basis Increased Trust is I could set up an Irrevocable Trust for my wife and our children and make my father-in-law a beneficiary and give him the power to appoint the trust assets to creditors of his estate, with the approval of my next-door neighbor, who will never approve. But because of that provision on my father-in-law’s death, all the assets in that trust can get a Step-Up in Basis. So step right up. That is where it is happening right now. Hamden Baskin: I have a question from the gallery on the Community Property Trust. Can the Community Property Trust be revoked or dissipated in a dissolution of marriage action? Alan Gassman: The statute is very specific that on a dissolution of marriage action, the assets of the trust go to the spouses equally and jointly exactly 50/50. So that is solved by the statute itself. That can be overridden by a marital agreement. But I would not recommend overriding it with a marital agreement because that could interfere with your stepped-up basis under the federal basis rules. Hamden Baskin: We’ve got a couple more minutes with you, Alan. I think it would be of interest for you to talk a little bit about charitable giving. I think that works into a lot of our estate planning. So if you can kind of do the same thing to tell us what is hot, what is not for charitable giving? Alan Gassman: What is really hot is the ability for a married couple who does not itemize to write off $600 in direct donations, either to a public charity or their own private operating foundation. If your wealthy clients like charity, they could go make $600 gifts to 10 different married couples who they love and suggest donations. The married couple can give the $600 to a charity and get a tax deduction. So I think that is nice. The bigger news is that 2020 and 2021 are the only years in recent tax history, or you can get a 100% of adjusted, gross income, income tax deduction. If you have a lot of assets in an IRA, that IRA is going to get taxed. When you die, maybe twice because of the estate tax, if you are over 70 and a half, then you are aware that you can move up to a hundred thousand a year from your taxable IRA to charity. But this year you could move your entire IRA. If I have a $10 million IRA and I am over 59 and a half, I can make a withdrawal that causes $10 million of income tax. I write a check for $10 million to my favorite charity, and that is all tax-deductible. So you represent charities. You are on charitable boards. You know who these people are, who always give a hundred a year out of their IRA. You want to go and approach them. Let them know that even though their spouse is not 70 and a half, yet if they are over 59 and a half they can do it too. And let them know that it is unlimited for this year only. If they pull money out of the IRA and they give appreciated stock and not cash, then they are going to say that much more. So, if you have any client who was going to die and leave a lot to charity, you need to have a serious conversation about why it is not going to charity earlier to save them income tax. In addition to the estate tax. This is a big, big opportunity you have here. Hamden Baskin: Alan, we have another question from the gallery, going back to the Community Property Trust, what would happen to the trust once the second party dies? Alan Gassman: It would be based upon the terms of the trust that you draft and who the beneficiaries are. It would pass to them. Whatever the right it can lock in for the children, which is what we should all be doing. Whenever the client is about to sign and leave, say, by the way, do you realize that when one of you dies, here is how much is going to the survivor that they can blow on the next sibling’s relationship? And then the, oh, really? Oh, we didn’t realize that. We didn’t know that, what can you do about it? Well, it is not easy. It is not inexpensive, but it should be considered. And it can all be rolled into that Community Property Trust or that Joint Exempt Step-Up Trust, but not a Tenancy by the Entireties Trust. That has to go all to the survivor and then they can use it for any silly reason they want. Hamden Baskin: Got it. Well, that segues then into maybe another short vignette concerning income tax planning, some of that you have kind of touched on, but you know, talk to us a little bit about income tax planning. If you could. Alan Gassman: Okay. The first thing I want to say is that very often clients come to me with a pension or profit-sharing plan, or they explained that their advisors told them they were not a good fit for a pension or profit-sharing plan. I get their census, I get their pension profit-sharing plan information. I send it to a good actuary. That actuary reviews it and makes proposals at no cost. I look like a genius and six times out of 10, you can improve what they had when they walked in the door. All you have to do is help them ask the right question. The second thing on the pension plan. It used to be that a plan had to be in place by December 31st of the calendar year for your S-corporations and your professional C-corporations. That is no longer the case. You now have until September 15th of the next year, if you file extensions. So jump on those pension plans. Even though the CPA said the business is the best one. The broker advisor said it is the best one until you ask a good actuary, it is probably, or quite possibly not the best one. The second thing to look out for is if you think the tax rates are going up next year, which they might. If you think they are going up and you may want to go ahead and accelerate your income this year, and you would do that by transferring your accounts receivable out of your professional corporation to you. So count them as if they were cash that came in this year. If you think that rates are going up and if you think you would not be able to do as good, a pension plan under whatever laws we face next year would be a fine option. Otherwise, income tax planning is pretty much unchanged. It is the same as usual, with no significant changes for next year. Please budget personally, you may be paying a 3.8% tax on your dividends and distributions that you take out of your S-corporation budget for that, that is I think a very realistic thing. I think cinema did not really have the chance to vote on that one. That one would be a big revenue raiser, and the perception that wealthy people who make 400,000 a year, you pay that 3.8% tax on every dollar above that I think that is quite possibly coming. Hamden Baskin: Well, thank you. Alan, thank you so much. Those are great things for us to know about. I think there was a lot of activity on the community cross. Alan also has free Saturday seminars for estate planning and other great topics you can get on his list as he follows up on these topics by emailing him at agassman@gassmanpa.com.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Article 3Part II: Reducing Estate and Trust Litigation Through Disclosure, In Terrorem Clauses, Mediation, Arbitration and Pre-Mortem Probate

Written By: Jonathan Blattmachr, Esq., Principal, ILS Management, LLC, and slightly tweaked by Alan Gassman. Excerpt from the 47th Annual Notre Dame Tax & Estate Planning Institute Outline Mr. Blattmachr is a Principal in ILS Management, LLC and a retired member of Milbank Tweed Hadley & McCloy LLP in New York, NY and of the Alaska, California and New York Bars. He is recognized as one of the most creative trusts and estates lawyers in the country and is listed in The Best Lawyers in America. He has written and lectured extensively on estate and trust taxation and charitable giving. Mr. Blattmachr graduated from Columbia University School of Law cum laude, where he was recognized as a Harlan Fiske Stone Scholar, and received his A.B. degree from Bucknell University, majoring in mathematics. He has served as a lecturer-in-law of the Columbia University School of Law and is an Adjunct Professor of Law at New York University Law School in its Masters in Tax Program (LLM). He is a former chairperson of the Trusts & Estates Law Section of the New York State Bar Association and of several committees of the American Bar Association. Mr. Blattmachr is a Fellow and a former Regent of the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel and past chair of its Estate and Gift Tax Committee. He is the author or co-author of several books and more than 400 articles on estate planning and tax topics. Among professional activities, which are too numerous to list, Mr. Blattmachr has served as an Advisor on The American Law Institute, Restatement of the Law, Trusts 3rd; and as a Fellow of The New York Bar Foundation and a member of the American Bar Foundation. Part I was in our last Thursday Report. CLICK HERE TO ACCESS PART I. Part II: In Terrorem Clauses Until well into the twentieth century, almost all property passing at death was transferred by Will. However, now significant wealth (often the majority of wealth of an individual) is transferred at death by other means. This wealth includes life insurance proceeds, pension and similar benefits and payable-on-death accounts which in some ways operate as a revocable trust does. In fact, in many jurisdictions, the “preferred” method to transfer assets to others at death is through a revocable (also known as a “living” or “inter vivos”) trust. However, considerable property continues to be disposed of by Americans by their Wills. Greed and other motives often resulted in attempts to influence the person who executes the Will (commonly called the “testator”) to transfer all or a significant portion of that wealth to certain individuals or institutions. Outright fraud was (and is still) not uncommon with respect to the preparation of an individual’s Will. The law has attempted to create barriers to prevent fraud with respect to such documents and to attempt to ensure the document reflects the conscious and actual wishes of the property owner. One is the Statute of Wills. Generally, it is a state statute requiring that the Will be executed in accordance with strict formalities, including, as a general matter, that it be in writing, be declared by the testator to be his or her Last Will and Testament and be witnessed by disinterested persons (that is, those who would take no financial interest under it). Many people do not execute Wills. As a result, all states have a default disposition scheme, called “intestate succession” (often referred to as “intestacy laws” or simply “intestacy”). Intestacy laws provide for the property to be inherited by those whom the state legislature believes are the ones the property owner would wish to receive his or her property in the event of death. Typically, these are the surviving spouse and descendants, descendants alone if there is no spouse, parents if there is neither a spouse nor descendants and so on. These individuals are commonly called heirs-at-law, next-of-kin, intestate takers or distributees. Generally, if an heir-at-law does not receive under the instrument offered to be proved (or probated) as the property owner’s Will at least as much as he or she would have received in intestate succession, he or she has legal standing to challenge the instrument offered for probate (that is, to contend it is not a valid Will, in whole or in part). Even if he or she does receive at least as much property under the instrument offered for probate as much as he or would receive if there were no Will, the intestate taker may have standing to challenge the Will for other reasons, such as the form of disposition (e.g., that the inheritance is in trust and not outright as it would be under the intestacy laws), or the nomination of someone as the executor of or trustee under the Will. Probably, the failure to receive at least as much under the proffered Will as the distributee would receive in intestacy is the principal reason to challenge the document (that is, to contend that it is not the decedent’s Will). Obviously, such a challenge may well reflect a financial interest in the decedent’s property but it often also reflects an emotional one as well. A child who, under the instrument offered for probate, would receive less than his or her sibling may feel emotionally “disinherited.” That is, the child perceives that the document reflects lack of equal love and respect that has been bestowed on his or her brother or sister or someone else. To attempt to prevent an heir-at-law from challenging the instrument offered as the property owner’s Will (such distributee called an “objectant” or “contestant” because he or she is objecting to or contesting the admission of the document to probate), that instrument may provide that an objectant will forfeit any disposition it makes in his or her favor. Such a provision is intended to frighten or terrorize any distributee from objecting and is commonly called an “in terrorem,” “disinheritance” or “forfeiture” clause, and those terms are used interchangeably in this article. Usually, such a provision states that any objectant will be treated as though he or she predeceased the testator (often without descendants if even the objectant has one or more descendants), if he or she challenges the instrument. An in terrorem clause, quite obviously, is ineffectual to cause the disinheritance if the instrument is denied probate. In other words, if the instrument is not proved to be the Last Will and Testament of the property owner, the disinheritance provision it contains will have no force or effect. Also, the extent to which an in terrorem clause is enforceable depends upon state law. Some states, such as California and New York, enforce them without limitation. In general, states that have adopted the Uniform Probate Code, enforce them only if the objectant did not have a reasonable basis to object to the admission of the Will to probate. Other states, such as Florida, do not enforce them. If the individual is domiciled in a state that limits or prohibits the enforcement of such disinheritance clauses, such a provision might be made enforceable against his or her heirs-at-law by directing the instrument to offered to original probate in a state that will enforce them. Alternatively, the individual may place his or her assets (or almost all assets) into a revocable trust to be governed by the law of a state that will enforce such forfeiture provisions in such a trust. Many reasons have been cited to use arbitration or mediation especially with respect to estates and trusts. These include reducing costs and time to resolve a dispute, privacy and to avoid the nearly inevitable results of hostility (or enhanced hostility) that individuals develop in litigation toward the other party or parties. It has been suggested that the latter point (that is, minimizing personal animosity toward the other party or parties to the dispute) is especially important in trust and estate matters on account of the probability that the parties are family members. And it is likely a reasonable observation that few, if any, individuals want their wealth to be the source of generating disputes among surviving family members or between beneficiaries whom the property owner has selected to enjoy the benefits of his or her wealth and the fiduciaries selected by the property owner to manage and care for it. Nevertheless, as indicated, preventing the beneficiaries from exercising their full rights and remedies under the law deprives them of the opportunity to use the full panoply of these rights and remedies that law would otherwise bestow of them to remedy a perceived wrong. And, as indicated, at least some states, such as Florida, limit the extent to which an individual may through a disinheritance clause limit these rights. As explained below, a disinheritance or forfeiture provision might be used as a key element in causing individuals to use mediation or arbitration to resolve disputes. In fact, although it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the matter in detail, such a provision in a Will might also be used to prevent other disputes relating to the transfer of property transferred at death other than by Will, such as by a designation of a beneficiary to receive retirement plan interests belonging to the decedent. Part III: Methods of Reduce Disputes Depending upon the jurisdiction involved and the goals the property owner seeks to achieve, it seems there are at least six methods that may be available to reduce the risk of litigation with respect to trust and estate matters. 1. Advise Inheritors of Inheritance Plans. Although Will and related “contests” are often about claims to wealth, the litigation often includes an element of perceived entitlement. And that feeling of entitlement is based upon emotional feelings. More than one a child who has been partially or totally disinherited–that is, does not receive at least what would be his or her intestate share (or at least a share as large as others)–has said something like, “Mother loved me as much as she loved you. So she would not have voluntarily given you more. You tricked her. And you cheated me and my children.” Occasionally, a child will perceive that he or she had an extra need that the parent wanted to fulfill. That happens, for example, where one child lives with the parent and another (or the others) do not. The stay-at-home child views the parent’s residence as his or her own home and has an expectation that he or she will receive that asset as well as an equal share of the balance of the estate. Unless the parent provides for the child to receive the home, that child may perceive that the parent was duped. Typically, the complaint is against another sibling even if the other sibling received no more of the estate than the stay-at-home child. Sometimes, the complaint is lodged against the attorney who prepared the Will or against another advisor (such as the individual’s accountant or financial counselor). Regardless of whether the complaint is spurred by a failure to receive an equal share or failure to receive more than an equal share, telling the children (or others) ahead of time what their shares in the estate will be may reduce the risk of a post-mortem dispute. A child or other inheritor, who is displeased with the advice, especially if it is given long before death, has many opportunities to try to change the outcome. In some cases, the advice is given initially verbally. A parent, for example, may tell the child who will receive less than an equal share that the parent is discriminating in favor of another child on account of a perceived additional need of such other child. This may be less likely to cause anger if the parent states that the other child who will receive more does not know about it. However, advising a child that he or she will not receive an equal share may have adverse effects even if it prevents litigation after death. For example, the child may refuse to communicate with the parent and may turn against the other child who will receive an enhanced share even if that other child is unaware of the plans for providing an unequal disposition of wealth. When the reason for the reduced or total disinheritance is because the parent perceives the child with disfavor, such as where the parent and child do not communicate (or when they do it is contentious), advising the child may be appropriate. There seems to be little downside to doing so. Whether the reason should be communicated to the child is debatable. The child may contest the disposition on the ground that the parent was acting under a delusion or claim while the parent is alive that he or she is incompetent and the child should be appointed as his or her guardian. In some cases, the “spillback” may be lowered if the lawyer for the child makes written communication advising the child (perhaps, through the child’s own attorney) of the inheritance plan. In any case, the lawyer may invite the child to have his or her own legal counsel contact the testator’s lawyer to discuss the matter. The fact that the parent’s lawyer is involved tends to show it is not a whim or the result of a delusion and may reduce the risk that there will be a perception of unfair play by the family members who receive enhanced shares. Another option may be not just to advise the potential contestant of the property owner’s plans for disposition but to enter a contract with that person that he or she will not object to the validity of the document or otherwise challenge it. Such a pre-death contract seems enforceable but the states vary widely as to how much consideration must be provided to make it enforceable. In at least some jurisdictions, it seems that the person releasing the claim must receive “fair consideration.” It seems extremely difficult to determine what fair consideration would be. Hence, it seems “risky” at best to rely on such a pre-death contract to avoid Will contests and similar challenges. However, use of a pre-death contract might be used to obtain consent to mediation or arbitration, as discussed below. 2. Use a Revocable Trust in Lieu of a Will. A Will becomes operative only when the testator dies. It typically has no practical effect during lifetime. It seems to be more credible to contend that the decedent did not know the contents of the Will or that it does not reflect his or her true wishes than a document that has impact during his or her lifetime. A revocable trust, especially if funded with substantial assets during lifetime, seems more difficult to challenge on the ground that the individual was unaware of its terms. Usually, after creating such a trust, the property owner will have assets retitled into the name of the trust, a tax identification number for the trust may be acquired, tax returns and other tax forms may have been filed by the trust, insurance in the name of the trust may be obtained (to insure assets the trust owns) and other action may be taken that demonstrates that the property owner is aware of the trust’s existence if not its post-death effects. In some cases, such as where life insurance is acquired by or transferred to the trust, the insurance company will ask for a copy of the trust or a description of it. Again, such action may reinforce that the property owner is fully aware of the trust and its terms. Also, as a general rule, a trust is valid even if not executed in accordance with the formalities of a Will. Furthermore, when the grantor of the trust dies and the trust becomes irrevocable, no lawsuit need be commenced to “prove” the document in order to make it effect in transmitting property. Finally, it seems that a property owner, in general, has significantly greater flexibility in choosing the law that will govern the validity, construction and effect of the trust than of his or her Will. As a consequence, it seems that the validity of a trust created during lifetime is less likely to generate challenge than may the validity of a Will. Another possible step to take is to make the trust amendable or revocable only with the consent of an independent person. A recital in the instrument that it the individual has thoroughly considered the terms of the trust and feels so strongly that they are what he or she wishes that he or she has decided to permit change only if an independent person approves may reinforce that the instrument does express his or her true wishes. 3. Use an Irrevocable Trust In Lieu of a Will or Revocable Trust. An even further step would be to make the trust irrevocable. As described above, a lifetime revocable trust both from a practical perspective (e.g., no lawsuit needed to be commenced to prove its validity) and theoretical one (e.g., no or fewer formalities as a general rule needed to make the trust valid as there is for a Will) is less likely to be challenged as invalid than is a Will. An even more assured manner to reduce the risk of a challenge to the validity of the document and reduce the risk of an effective challenge may be to make the trust irrevocable. Even though irrevocable, the transfers of property to the trust need not be subject to gift tax. Many irrevocable transfers in trust, such as where the grantor may “change the interest of the beneficiaries as between themselves” or “revest the beneficial title to the property in himself” or herself are not subject to gift tax because the transfer is regarded as incomplete for such purposes. The transfer also is incomplete and, therefore, not subject to gift tax, even if the transfer is irrevocable, and the grantor retains no power to change the interests of the beneficiary but is eligible, in the discretion of another person as trustee, and not entitled to any distribution from the trust if, under local law, the grantor’s creditors may attach the assets in the trust. Indeed, under the law of most states, a creditor of the grantor may attach the trust assets to the extent the trustee may distribute property to the grantor even if the grantor has no intent to delay, hinder or defraud creditors when transferring property to the trust. However, a grantor may (or, if any part of a transfer to the trust is a completed gift, must) file a United States Gift (and Generation-Skipping) Transfer Tax Return (IRS Form 709) reporting the transfer and attaching a copy of the trust agreement even if the transfer is incomplete. Even if the taxpayer is relatively confident the transfer is not complete, filing a Form 709 may permanently resolve that issue. If no return is filed or if the transfer is not reported on it (even if the taxpayer has a reasonable basis that no reporting of the transfer is required), the statute of limitations to impose gift tax with respect to the transfer never commences. In fact, significant detail about a transfer that the taxpayer believes is not subject to gift tax (because it is incomplete or otherwise) must be disclosed in detail to cause that statute of limitation to begin. That kind of detailed disclosure likely is evidence of knowledge of the disposition and that it was intended. In fact, making a transfer to a trust a completed gift, upon which gift tax is paid, likely constitutes further evidence of an intent to make precisely the transfer involved and which is described on the gift tax return. And, a transfer to a trust may be complete even if the grantor is a beneficiary to whom another as trustee may, as a matter of discretion, make distributions, if the trust is created under the law of the state under which the creditors of the grantor may not attach the trust assets. Alternatively, the property owner during lifetime could transfer property outright to persons (or in irrevocable trusts for their benefit) disclosing the transfer on a gift tax return. That likely reduces the risk of any challenge to such dispositions and the likely success of any made. However, most individuals do not wish to transfer all or a significant part of their wealth prior to death. Hence, such completed gift strategies, especially if they will generate the payment of gift tax, are unlikely to be employed to avoid post-death disputes among beneficiaries. Nevertheless, as discussed above, it seems that a successful challenge to the validity of a document is less likely if it is a lifetime trust, which has been significantly funded, rather than if a Will is used. It also seems that a successful challenge to specific provisions also may be lower if the instrument is such a trust rather than a Will. For example, if the grantor of the trust has his or her chosen successor trustee act as trustee during the grantor’s lifetime either alone or with the grantor, it should be much more difficult to contend that the grantor did not intend that person to be the successor fiduciary to act upon the grantor’s death. Furthermore, even dispositions in a lifetime trust may be harder to challenge. For example, if the property owner dies in a jurisdiction that has the traditional rule against perpetuities, violation of that rule may void the disposition. Having the law of another jurisdiction govern the validity, construction and effect of the instrument, which jurisdiction has “softer” rules (such as no rule against perpetuities), may limit the grounds for challenge. Similarly, alternative rules of evidence, etc. also likely can be controlled by using a lifetime trust rather than a Will. 4. Use an In Terrorem Clause. When the child (or another intestate taker) is to receive what is likely to be perceived as a significant although not equal share, a disinheritance clause usually will help to reduce the risk of litigation arising. If the property owner lives in a state that will not enforce such a clause, he or she may consider directing the admission of his or her Will to original probate in a state that permits that and will enforce such clauses. Much of the litigation involving estates and trusts is other than a “Will contest,” that is, a challenge to the validity of the document. It may be a construction of the instrument, the choice of fiduciaries and how the fiduciaries administer the estate or trust. In order to reduce the risk of such litigation, an in terrorem clause may be considered and which would provide a forfeiture of benefits under the document if any such a challenge is made. However, even in those states which uphold disinheritance provisions for the successful challenge of a Will, it may not be certain that such disinheritance or forfeiture clause may be used to deter other litigation, such as a challenge over certain fiduciary actions. Just as a challenge to the validity of a trust created during a lifetime may be less likely to occur and be less likely to be successful than the challenge to the validity of a Will, it seems that it may be possible to use a disinheritance provision in a trust, which is made subject to the laws of a state that will with great certain enforce a forfeiture provision, with respect to more than just an attack on the instrument’s validity. For example, as noted above, under Alaska law, a provision in a trust purporting to penalize a beneficiary by charging the beneficiary’s interest in the trust, or to penalize the beneficiary in another manner, for instituting a proceeding to challenge the acts of the trustee or other fiduciary of a trust, or for instituting other proceeding relating to the trust, is enforceable even if probable cause exists for instituting the proceedings. This broad authority given to an individual who creates the trust under Alaska law seems powerful and has been used by some attorneys to prevent almost certain litigation against the validity of other documents (including a threatened challenge by a spouse to a prenuptial agreement entered with the decedent), against fiduciaries or against other family members. Summary and Conclusions The level of legal disputes involving trust and estate matters is significant. In some cases, the legal system itself (such as requiring the commencement of a lawsuit in order to have an instrument admitted to probate as a decedent’s Will) aggravates the conditions for such disputes to arise. Although most of the actions involve claims for money or other property, claims arising with respect to trust or estate matters usually are among family members and, therefore, they typically involve emotional matters. Emotions often make compromise more difficult to achieve. Also, the American level system generates animosity among those litigants involved, often resulting in the ceasing of any further communication among the family members involved. Avoiding bitter and protracted litigation among family members almost always will be the desired goal of a property owner. It seems that using certain mechanisms, such as using a trust governed by the laws of a jurisdiction, such as Alaska, to transmit wealth, may reduce the risk of such litigation on account of the enforcement of forfeiture clauses if a beneficiary undertakes certain action. However, some property owners will not wish to use such a harsh “stick” to avoid protracted litigation. Rather, they will wish the parties to settle disputes through good faith mediation and/or arbitration. The consensus among commentators appears to be that mediation and arbitration usually are far preferable to court litigation but that there is no practical way to cause potential litigants to participate in such alternative dispute resolution absent their agreement or absent a statute that will enforce a mandate under the instrument that will be subject to the litigation. However, even legislation that authorizes mandatory mediation or authorization would not seem to apply with respect to the validity of the document itself, although terrorem clauses are enforceable in many American jurisdictions even as to challenge of the validity of the document that contains it. And it seems that inducing the use of mediation and/or arbitration can be effected either by using a forfeiture provision or conditioning the grant of beneficial interest by requiring a binding agreement by the party to mediation or arbitration. One alternative is pre-mortem probate in those states that permit it or, for those residents elsewhere, in Alaska. *This paper is derived from Blattmachr, “Reducing Estate and Trust Litigation Through Disclosure. In Terrorem Clauses, Mediation and Arbitration,” Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 9, No. 2, Spring 2008. Jonathan G. Blatttmachr is the Director of Estate Planning for the Alaska Trust Company, a principal of Pioneer Wealth Partners, LLC, in New York, New York, Editor and co-developer of Wealth Transfer Planning, a computerized system for lawyers, published by Interactive Legal Systems, LLC, in Melbourne, Florida. He is a former member of Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP, and of the Alaska, California and New York bars. He also is the author or co-author of seven books and over 500 articles.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For Finkel’s FollowersHow To Stop Doing Everything Yourself |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Forbes’ CornerWhat Estate Planning Should You Do Now That Congress Might Not Change Anything?

Written By: Martin Shenkman Nov 1, 2021 Congress has debated wide-ranging estate tax changes and now the latest proposal is for no estate tax changes (although trust income taxation is impacted significantly). What steps should you take given the uncertainty?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

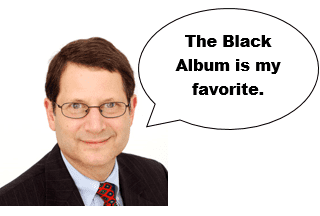

Featured EventFREE ESTATE TAX PLANNING WEBINARSaturday, November 20, 202111:00 AM to 12:00 PM EDTPresented by: Alan Gassman and Brandon Ketron Please join Alan Gassman and Brandon Ketron for this 60-minute discussion of planning opportunities that apply for Floridian “Snowbirds” and other affluent Floridians to maximize flexibility while favorable estate tax law opportunities are still available. This notably includes Spousal Limited Access Trusts and Dynasty Trusts that are used to void estate taxes, Community Property Trusts that can be used to avoid capital gains taxes after the death of a spouse, and the many other alternatives that exist for well-represented clients. REGISTERRegister for Planning For The Affluent Floridian on Nov 20, 2021 11:00 AM EST by clicking the REGISTER button above. After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the webinar. This program does not qualify for Continuing Education Credits.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Upcoming EventsRegister for all future free webinars from Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A. using this link

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

YouTube LibraryVisit Alan Gassman’s YouTube Channel for complimentary informational webinars and more!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Humor

(Pictured above) Attorney Alan Gassman at work. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A. 1245 Court Street Clearwater, FL 33756 (727) 442-1200 Copyright © 2021 Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||