March 28, 2013 – Hesch – Porter Interview Continued

THE HERSCH-PORTER INTERVIEW CONINTUED – VALUING APPRAISALS: A CONVERSATION

WITH JERRY HESCH AND JOHN PORTER ON THE IMPORTACE OF APPRAISALS IN THE

CONTEXT OF ESTATE PLANNING STRATEGIES

JOINT TRUST ARTICLE

UMBRELLA LIABILITY POLICIES

OUR FREE ESTATE TAX PLANNING SOFTWARE

J-1 VISAS – WHAT DO THEY MEAN FOR PHYSICIAN ADVISORS?

We welcome contributions for future Thursday Report topics. If you are interested in making a contribution as a guest writer, please email Janine Ruggiero at Janine@gassmanpa.com.

This report and other Thursday Reports can be found on our website at www.gassmanlaw.com.

The Hesch-Porter Interview Continued

SELECTING, DRAFTING AND IMPLEMENTING VALUATION ADJUSTMENT CLAUSES – LESSONS FROM THE GRAND MASTERS

Thank you for the wonderful feedback on the interview excerpts that we published last week on discount and appraisal planning.

This week’s interview discussion is on valuation adjustment clauses and whether to use a “Wandry” clause or a “King” clause or no clause at all when making gifts or family sales of closely held entity interests, and alternatively, the advantages of having a charity involved and using a Petter arrangement. Our favorite clause is the Santa Clause.

The following is a transcribed excerpt from a Bloomberg/BNA webinar that Alan Gassman and Chris Denicolo gave with John Porter of the Baker Botts law firm, and Professor Jerry Hesch of the Berger Singerman law firm and of the University of Miami, on March 7, 2013 entitled “Don’t Discount Discounts.”

Alan Gassman: We’re going to talk about what we are calling the “Wandry Clause, ” which is a type of valuation adjustment clause. The Wandry case deals with the ability to make gifts without designating a specific number of shares or percentage of ownership of an entity, but instead a number of shares or a percentage equal to the value that you’re looking for.

Jerry, when you and your partners are doing work now with entity transfers, are you using these “Wandry Clauses” or are you designating a number of shares or a set percentage?

Jerry Hesch: That’s an interesting question Alan. A lot of people are saying that we can now rely on Wandry. The IRS did not appeal the Wandry case, which is very important to note. The IRS probably doesn’t like the Wandry clause, and because they don’t like the Wandry clause they don’t want a court of appeals affirming the lower court’s decision.

Consequently, what the IRS probably decided to do was wait for somebody who used one of these defined value clauses in a factual situation where they mess it up. The kind of case that will be easy for the IRS to win, so the IRS will look to set a good precedent in a taxpayer case where the facts are bad.

Do not tell your clients that you can guarantee use of the Wandry clause. I also caution against recommending that clients use their full gift tax exemption. I always like to leave several hundred thousand dollars out just in case the IRS will be successful in reducing the size of the discount and therefore increasing the size of the taxable gift or increasing just the value of the asset. I like to keep a little bit of exemption in reserve in order to make it clear.

The other problem I have with the Wandry clause is it can become confusing when trying to explain it to the layperson. I really have no preference between the type of defined value clause. In order to make it easier to communicate the options, I give the client an illustrative, hypothetical example showing the size of their potential discount. Say we valued it at $2,000,000, but the IRS comes back and successfully values it at $2,500,000. What would be the impact on the size of the gift? What would be the impact on the number of shares or the interest transferred?

Alan Gassman: In other words, the key to successfully advising clients is not just what you know, but also your ability to communicate information that we as planners take for granted but is very complex to the client. It is important to break it down for them in a very simple manner.

Jerry Hesch: Yes, exactly. So in looking at this situation, the most conservative route is to transfer a fixed number of shares or a specified percentage of ownership. In this case, you don’t have to have an exact value at that time and you get the appraisal report. Let’s say that the appraisal report says the fixed number of shares is worth $4,000,000. The IRS comes back and says those shares are worth $5,000,000. You compromise at $4,500,000, so you just increase the size of the gift. That’s the easiest and most conservative approach, and also the simplest for the client to understand.

Alan Gassman: What about this other option of transferring based upon a formula clause?

Jerry Hesch: I think transferring a number of shares equal to a value that you want to gift is also viable. I always look at what is done in the real world. When we do buy-outs and business transactions, we have these kinds of formulas where somebody is selling an interest in the business and wants $5,000,000, and the buyer’s percentage is variable rather than fixed, but the dollar amount is what determines the ownership percentage.

What’s important to note is that if you look at Internal Revenue Code Section 2703, it has incorporated or codified a basic common law principle that says “We will not accept whatever you do for interfamily transactions unless you can show it is also done in the real world between unrelated third parties whose interest may be adverse.”

I think that the defined value clause where you reduce the number of shares is viable, and there should be no reason why it doesn’t work. The more conservative route is to fix the number of shares and just increase the value later, which is what you’ll always keep the gift amount below a certain amount to leave a buffer.

Alan Gassman: Thanks for that insight Jerry. Now we’re going to turn to John. I know you have a lot of detail to offer on these clauses John, but from a real world perspective, what are you doing for planning in these kinds of situations? What is going on here and how are you and your partners doing in light of Wandry and the other cases?

John Porter: I think it really depends, Alan. A lot of this is about educating the clients, because most of them don’t know what these formula clauses are, and talking through the issues. For example, do you have a client who has charitable intent? If you have a client with charitable intent like the clients in McCord, in Petter and in Christensen, my view is that the best formula that you can use is one that comes from those cases. Of course, we’ll talk about the differences in McCord and Petter, because there are some, but I think those are what I’d call tried and true.

We’ve got blessings on both the Petter side and the Christensen side from the Tax Court and the 8th and 9th Circuit of Courts of Appeals, and on the McCord side we’ve got the 5th Circuit as well. Wandry is certainly another option for clients who are not charitably inclined, and we have done some of that planning. I’m not an estate planner per se, but I’m involved in a number of estate planning projects advising clients.

Alan Gassman: Do you have a technique you prefer instead of the “Wandry Clause”?

John Porter: My preference would be that in lieu of Wandry, clients who are now charitably inclined might consider a Petter-type transaction, but instead of having a charity receive what I call the value above the dollar value formula, you could either have a GRAT or a QTIP Trust. However, there are issues associated with both of those.

There are a large number of tools in the estate planner’s toolbox, and I don’t think one size fits all. I agree with Jerry. I like the Wandry decision. I think it’s well reasoned, but I certainly believe that the IRS is going to continue to try to challenge these transactions. The other thing that’s in the estate planner’s toolbox is the King clause, which is a consideration adjustment clause. We use that from time-to-time.

Chris Denicolo: John, I know that you have quite a bit of experience in the valuation adjustment clause arena, and our PowerPoint slides illustrate some of the main cases that have drawn the lines for us as to what has been acceptable by the courts. What are your thoughts on these cases and where we’re at now in this area of jurisprudence?

John Porter: I think we’ve come a long way since really the first case, which was McCord. Prior to that you had the Procter case and a line of cases that are in the materials: Ward, Harwood- all of which rejected the use of formulas. The lone case the taxpayers had was the King case, which was a value consideration adjustment clause.

The beauty of these formulas is that they are designed to allow the transferor to define the dollar value of hard to value assets passing to taxable transferees. One of the things clients like is certainty. They want to know how much they’re going to transfer, if it’s going to cost them any gift tax, and if so, how much. The goal of the formula transfer is to give the client as much certainty as possible in an essentially inherently uncertain world, which is valuation.

There are several types of clauses that can be used. There are various names that people put on them. One is the defined value clause based on values as finally determined for estate and gift tax purposes- that’s Christensen, Petter and Wandry. In those types of clauses you transfer let’s say a set number of units of the partnership to a group consisting of in Christensen and Petter, a group of taxable donees. There was a sale and a gift component to trusts that were created for Mrs. Petter’s children, and then non-taxable donees-charities. You define the value of the units going to the taxable donee, and everything else based on values as finally determined for estate and gift tax purposes goes to the non-taxable donee.

This type of clause is to be contrasted with what I call a defined value clause in McCord or in Hendrix, where you have a similar type of clause but it’s not based on values as finally determined. So what happens in those cases is after the transfer occurs the donees get together and agree among themselves, based on the formula, how to allocate the units pursuant to a confirmation agreement. Any change in value for gift tax purposes of the unit doesn’t affect the value of the unit each party receives, which is important because you contrast that to the Christensen/Petter type cases, where the value of the units going to each donee is in fact based on values as finally determined. Then if you get into an audit and you reach agreement with the IRS on the value of the units transferred, that can have an impact on the number of units that the charity receives. Or if you litigate that issue, the values as finally determined impact the number of units.

For example, in Petter they valued the units using roughly a 50% combined lack of marketability/lack of control discount. Shortly before trial, we settled with the government based upon a 35% discount. The result of that formula was to cause units to be shifted from the trust created for Mrs. Petter’s children to the charity. The charity got more units than was initially anticipated. It was fine for those clients- they were very charitably inclined and used donor advised funds- but the bottom line was it had an impact. Whereas in McCord, the government argued that the values should be different. The Tax Court determined that the values should be different, but when the Fifth Circuit looked at the analysis, what the Court said was that the McCords’ transfer was based upon the formula clause, and what they transferred to the taxable donees was units in the partnership having a specific dollar value. So ultimately, there’s an important distinction to be made in those types of clauses.

Alan Gassman: We have discussed the charitable arrangement that you described, and many clients do not want the complexity or charitable involvement this requires. Can you tell us about the King case?

John Porter: The King case is worth talking about because it was the only pre-McCord case where the formula clause was in fact respected. It’s a consideration adjustment clause where you transfer units and you take back either a note or cash is paid, and if the value of those units is finally determined to be different than what the parties anticipated, there’s an adjustment to the purchase price that’s paid. The Court in the King case said that in fact works, and the Tenth Circuit affirmed it. We use those in a number of situations where we don’t want to have a gift occur, and we’ve got some cases where the IRS has respected it in settlements and other cases where the IRS has pushed back. But fundamentally, based on the analysis in Christensen, Petter and Wandry, I think the King Clause ought to work.

Chris Denicolo: Thank you very much John. The Procter case is the seminal case in the defined value clause context. How does the Procter case fit in with what has recently occurred in valuation adjustment clause case law?

John Porter: What you have to worry about, and we’ll talk about this in the context of the Wandry case, is the Procter analysis. Whereas in Procter what happened was you had a transfer of a specific number of units, and the formula provided that if the value of the units caused any gift tax to be incurred, then those units causing the gift tax to be incurred would come back to the donor. The Court in Procter said that clause doesn’t work. It’s going against public policy because you’re asking the Court to basically issue a declaratory judgment, which ultimately would become moot once the Court made its determination, and it’s trifling with the tax system.

Now one of the things I like to tell people is Procter was decided in 1944. There are a lot of things that have changed since 1944. If you think about 1944, most of us on this line weren’t born. D-Day either had just occurred or hadn’t yet occurred before this decision was rendered, and a lot of water has gone under the bridge since then. Particularly in the formula clause area, where you’ve had many changes in the use of formula clauses: in the marital deduction context, in the charitable deduction context, you’ve got formula GST transfers, you’ve got formula transfers through a GRAT, and in each case, the formulaic adjustments are made only if the value of the transferred property is determined to be different than the originally reported value. So one of the arguments we’ve made in all of these cases is the landscape has changed, the public policy argument is very different. It’s hard for the government to make these public policy arguments when they themselves have Regulations that authorize the use of formula clauses. That being said, there’s language in the Petter decision which talks about Procter not working and the Petter type clause working.

Chris Denicolo: In the Wandry case, the IRS argued that the valuation adjustment clause was against public policy, but the court nevertheless upheld the clause used by the taxpayer. Why do you think the Tax Court sided with the taxpayer in this case?

John Porter: As we talked a little earlier, the cases where the taxpayers had success in the McCord and post-McCord era: McCord, Hendrix, Christensen and Petter all involved charities and charitable transfers. Until this last year, where you had a Tax Court Memo decision that many of us are familiar with called Wandry. Wandry is interesting because it is a formula clause very similar to the formula clause in the Petter case, except no charity is involved. So you see the language from the Wandry formula, basically noting that they were going to get a good faith determination of value by an independent third party appraiser. But if after the appraisal, and ultimately after audit, the value of the units gifted is determined to be different than what the parties anticipated, then the gifted units will be adjusted accordingly, so that the number of units gifted to each person equals the amount set forth in the dollar value transfer. Essentially what they were trying to do was transfer a sufficient number of units to use their remaining lifetime gift exemption and the annual gift tax exclusion. The government argued Procter, the taxpayer argued Petter, and the Tax Court in a memo decision said “We think Petter controls.” There’s nothing in the Wandry formula that is a reversionary interest. Now the IRS would say that’s the substance over form analysis, because essentially if there’s going to be an increase in value, then the units are coming back to the parents. But there’s a distinct difference in the language used in the Procter case compared to the Wandry case. In Procter, there was a specific number of units actually transferred, and a reversionary interest retained in it if the value was determined to be higher than what the parties thought. In Wandry, the language that was governing for state law purposes was “I’m transferring units worth a specific dollar value.” Now they tried to allocate those units preliminarily, subject to a final determination, but I think that distinction that the Court pointed out is a real one under state law, and obviously one that the Tax Court in its memo decision accepted.

There’s language that I would suggest using differently if you like using the Wandry approach. It’s this language that talks about if the IRS challenges such valuation and a final determination of a different value is made by the IRS of a court of law. I don’t know what a final determination of value by the IRS is, and so what language we like to use is “based upon values as finally determined for transfer tax purposes.” It’s language that you see in the Internal Revenue Code, it’s very commonly relied on language.

Chris Denicolo: Do you think that the Wandry clause is appropriate for most planners and their clients, or do you feel that other types of valauation adjustment clauses should be used as well?

John Porter: As I said earlier, I think that there are a variety of clauses that an estate planner has in their tool kit. What I like about these formula clauses is they give us something to argue at the audit level, or at appeals or in litigation, other than just whether the discount ought to be 30% or 50% or 25%. It’s a very strong argument, and the client likes these types of clauses in most cases because the goal is to allow them to have some level of certainty with respect to what they are in fact transferring. There are a variety of- and literally this is a two hour discussion- potential donees, what I’ll call the excess amount. I don’t like to say “the excess amount” per se, but you have the taxable donees and the non-taxable donees, and there are a variety of potential non-taxable donees or donees of the excess amount.

One is a public charity with a donor advised fund. That’s what was involved in Petter, Hendrix and McCord. I like those because of the language in the cases. If you read Petter, Hendrix and McCord, they talk about the fiduciary obligations that the charities have, and I think that’s some very strong case law. Private foundations are another possibility. That was an issue that was involved in the Hendrix case, but I think that’s more difficult because of the self-dealing and excess business holdings rules.

A lifetime QTIP is another option, as well as a GRAT. Of course, if the client doesn’t want that kind of complexity, then he/she might consider if you’re doing a sale or a consideration adjustment clause like you had in the King case. Or frankly, the Wandry case is out there. The government non-acquiesced, as Jerry pointed out, but right now we’ve got a nice Tax Court Memo decision that supports the use of that type of clause. So if the client’s going to do nothing other than that Wandry Clause, I think that’s good planning.

Chris Denicolo: Do you have any words for the wise for reporting transactions that use valuation adjustment clauses, or should they be reported no different than a transaction that does not use this type of clause?

John Porter: The thing that you want to ensure you do in reporting these formula transactions is to report the transaction consistent with the formula. I like to include the formula document in the gift tax return, and note that the transaction was pursuant to formula. Based on the formula and the valuation of the units, here is what we believe to be the number of units transferred. You want to avoid a problem that can occur where the taxpayer doesn’t report the transaction consistent with the terms of the formula, because that’s one of the taxpayers in the Knight case that’s in the slides, and certainly one of the things that the IRS is looking for in the context of formula clauses.

Alan Gassman: John and Jerry, we cannot thank you enough for your time and attention to these questions, and especially for John’s thorough analysis here.

Jerry Hesch’s contact information is as follows:

Jerome M. Hesch

Berger Singerman

1450 Brickell Avenue, Suite 1900

Miami, Florida 33131

Phone: (305) 755-9500

Fax: (305) 714-4340

jhesch@bergersingerman.com

John Porter’s contact information is as follows:

John W. Porter

Baker Botts

One Shell Plaza

910 Louisiana Street

Houston, Texas 77002-4995

Phone: (713) 229-1597

Fax: (713) 229-2797

john.porter@bakerbotts.com

We hope that readers will join us next week when we share what Jerry and John said recently about tiered discounts.

Joint Trust Article

We cannot wait to share our Joint Revocable Trust article.

Next week our first formal article on the JESTSM (Joint Exempt Step Up Trust) should be published on the Leimberg Information System (LISI) and will feature the chart that you can review by clicking here.

We believe that this system will maximize the probability of receiving a full stepped up basis on joint revocable trust assets on the death of the first dying spouse, and also the ability to fund one or more credit shelter trusts on the first death that can benefit the surviving spouse without being subject to federal estate tax on the surviving death.

We have coupled this arrangement with savings clauses and segregated subtrusts that we believe make this an extremely viable planning vehicle for many couples who have formerly been balancing separate revocable trusts in non-community property states such as Florida.

There are a number of technical issues that must be reviewed by anyone who plans to implement a joint revocable trust that may fund a credit shelter trust on the first death or provide a stepped up basis on assets other than a separate share or distinct half considered as held or owned by the first dying spouse.

With a 23.8% capital gains rate on high income clients and a 40% estate tax, we believe it is essential for Florida estate tax planners to understand the implications of these vehicles.

Private Letter Rulings have blessed the full funding of a credit shelter trust, but may have missed some issues that practitioners need to be aware of.

The same Private Letter Rulings denied stepped up bases, but in those situations the beneficial ownership interest of the surviving spouse was different than it can be under our JEST system.

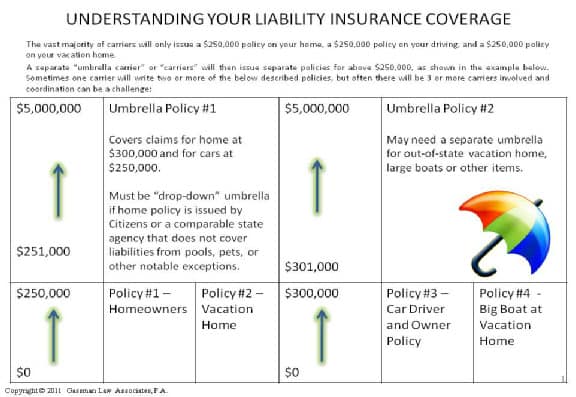

Umbrella Liability Policies

We find that clients are very appreciative when we point out that they do not have proper umbrella liability insurance coverage. If you share the attached materials with clients and use the form letter attached, click here, you will receive significant gratitude both from the clients and their insurance agents and other advisors.

By way of background, an umbrella liability insurance policy is insurance that is taken out on top of existing liability policies to greatly enhance the amount of coverage the holder receives. Typically, homeowners insurance will provide liability coverage up to about $250,000 and an automobile policy also has a common max of $250,000. Higher coverage is needed to successfully insulate the policy holder, since the maximum protection provided by most underlying policies is easily reached in any lawsuit. This leaves many people on the hook to pay damages out of their own pockets. Luckily, a single umbrella policy will pick up where the underlying policy stopped and provide additional coverage from $1,000,000 to $5,000,000, or in some cases higher.

New_Joint_Exempt_Step-Up_Trust_Chart.1b Form_Letter_Final

One umbrella policy will cover the separate underlying policies held for the home and cars. The umbrella policy is stacked on top of the underlying policies and treats the latter as a deductable. Say John held a homeowners policy for $300,000 with an umbrella policy for $3,000,000 and a visiting neighbor was injured by a falling light fixture causing $1,000,000 of damages. His underlying homeowners insurance would first pay its max of $300,000 and then his umbrella policy would kick in providing coverage for the remaining $700,000.

An important distinction to note when comparing umbrella options is whether the policy is “following form or drop down.” A following form umbrella policy will only provide coverage for the coverage that the underlying policy provides for. So if the underlying policy does not include pet liability or pool liability the umbrella policy will not either.

However, a drop down umbrella policy will normally cover items that are excluded under the primary policy. This can be essential when clients have underlined coverage with Citizens or other carriers that have significant limits on what they cover.

Umbrella policies can have many limitations. For example, if a second home is located out of state, it is normally necessary to procure a separate umbrella policy for each state where the client owns property.

Often these will be provided by separate carriers.

Another added benefit is that an umbrella policy will usually increase the holder’s uninsured motorist coverage. This allows the holder to claim on his own insurance for the damages he sustained from a wreck with an uninsured driver. This is quite handy to have since about 45% of Florida drivers are lacking adequate insurance and the umbrella can provide the needed relief that the underlying policy wouldn’t reach. Most importantly, an umbrella policy is a financial safety net. Being caught without it, even with an underlying liability policy, can subject you to a mountain of crushing debt.

Click here to view our webinar on umbrella liability policies.

Our Free Estate Tax Planning Software

Our estate tax planning software is progressing nicely.

Thank you to everyone who has tried this new software, which allows the user to dial factual variables up and down while seeing the resulting columns of numbers increase and decrease. This facilitates having each scenario pictured in the best way possible to help clients understand the dynamics of using credit shelter trusts versus portability, annual gifting, the impact of growth of investments at various percentage rates, inflation adjustments, discounted annual gifting, and the use of life insurance trusts.

Please send us an e-mail if you would like to be a beta tester for the GAC (Gassman Archer Crotty) Designer View software as it evolves.

You can’t be a beta fish but

you can be a beta tester!

J-1 Visas – What Do They Mean for Physician Advisors?

Many physicians have been educated overseas and then come to the United States for a residency to complete their medical degree training or a fellowship to complete post-medical degree training under a J-1 Visa. After the expiration of their J-1 Visa, the alien physician may want to stay in U.S.

In this article we will provide a brief explanation of a J-1 Visa, how to obtain one, and then explain how a physician with an expiring J-1 Visa may remain in the United States. Then this article will discuss provisions an employment agreement with a former J-1 Visa holder should contain.

J-1 Visa Basics

The J-1 Visa program is designed with the goal of cultural and educational exchange. The official name of the program is the Exchange Visitor Program. J-1 Visas are for foreign physicians who would like to participate in graduate medical education programs or training at an accredited U.S. school of medicine. In limited circumstances, a J-1 physician visa is available to an alien physician to study medicine outside of an accredited clinical program. But such circumstances still require the involvement of an accredited U.S. medical school or medical center, and under no circumstances may the alien physician provide patient care.

To obtain a J-1 visa, typically the applicant must first be accepted by the school to which the applicant will be attending. After being accepted and filling out some additional J-1 Visa specific paperwork, the school will transmit all of the student’s information to the U.S. Government Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS). Based on the transmitted information, SEVIS will create a form DS-2019 and send the DS-2019 to the alien physician’s local U.S. Embassy. Local embassies can be located online at the following link: http://www.usembassy.gov/.

After the U.S. Embassy receives the DS-2019, the alien physician can apply for a J-1 Visa with the local embassy. Applicants should start the process as early as possible because we all know how quickly the U.S. Government works. Once approved, alien physicians may move to the U.S. no more than 30 days before the beginning of their program. Extensions of a J-1 Visa are possible provided they are continuations of the alien physician’s education program.

Expiration of J-1 Visa

The main limitation on a J-1 Visa is that students are expected to return home for two years immediately after the expiration of their J-1 Visa. The goal of the J-1 Visa program is to promote “global understanding through educational and cultural exchanges.” After the expiration of a J-1 Visa, foreign physicians are not able to “(1) apply for an immigrant visa; (2) adjust status; (3) apply for an H or L nonimmigrant visa; or (4) change to almost any other nonimmigrant status within the United States.” Kurten, Benjamin T, Jennifer A. Minear, and Elahe Naifabadi. “Clinical J-1 Waivers–A Primer” Immigration & Nationality Handbook (2009-10): 611. This restriction is known as the 2-Year Home Residency Requirement.

Fortunately, there are ways around the 2-Year Home Residency Requirements. Alien physicians who wish to remain in the U.S. can apply for a waiver due to: (1) hardship to a U.S. citizen spouse or child; (2) potential persecution in the physician’s home country; or (3) the Conrad State 30/J-1 Waiver Program, the focus of this article.

Florida’s J-1 Visa Waiver Program and Your Contract

J-1 Visa waiver programs are administered by the states. Florida’s program is administered by the Department of Health State Primary Care Office. Florida permits up to thirty J-1 Visa Waivers per year. Applications may take months to process, so applicants should pursue the J-1 Visa Waiver program with the Department of Health and their prospective employer well before the expiration of their J-1 Visa.

Physicians applying for a J-1 waiver must meet a number of requirements. One of the most important is that the contract must be to work in a medical practice that is located in a federally designated health professional shortage area or medically underserved area or population. Applications for a J-1 waiver to work in a location that is not a shortage area or underserved area will only be considered if there are waivers still available after all shortage area and underserved area applications are considered. You can click here to find out if an address is in a designated health professional shortage area or medically underserved area or population

In addition, physicians must agree to work for a period of three years. Employment must be full-time and, generally, the medical work being performed must be considered “medically essential.” In other words, waivers are not permitted for cosmetic surgery. For additional guidelines, click here for the Florida Department of Health’s most recent publication on the J-1 Visa Waiver Program.

Non-competition covenants are not prohibited by the J-1 Visa Waiver Program.

Any Employment Agreement with a J-1 Visa Waiver position should cover the following topics to assure compliance with the Florida Department of Health and approval of the physician’s waiver application.

1. Name, location, and Tax Identification Number of the practice in the health professional shortage area or medically underserved area or population.

2. Minimum duration of three years.

3. Full-time employment: physicians must work at least 40 hours a week, exclusive of time that is spent on-call, on inpatient care, on hospital rounds, on emergency room duties or on travel. Of the 40 hours, at least 20 hours must be providing primary care.

4. Transfer from a site other than listed in the initial application: not permitted unless prior written approval from DOH.

5. Compliance with DOH regulations: a catchall that the physician will be responsible for compliance with matters related to the submission and review of the application, including providing all of the materials other than the employment contract to the Florida Department of Health.

We welcome any questions, comments, or suggestions for this article.

APPLICABLE FEDERAL RATES

To view a chart of this month, last month’s, and the preceding month’s Applicable Federal Rates, because for a sale you can use the lowest of the 3 please click here.

SEMINARS AND WEBINARS

SEMINARS:

PLEASE SET YOUR CALENDARS TO JOIN DENIS KLEINFELD, MICHAEL MARKHAM, ALAN GASSMAN AND OTHERS FOR THE ANNUAL FLORIDA BAR WEALTH PROTECTION SEMINAR WHICH WILL BE HELD AT THE BEAUTIFUL HYATT REGENCY IN MIAMI, FLORIDA. If you have never attended this event please give it a try. A good many attendees never miss it.

THURSDAY, MAY 16, 2013

The Florida Bar Annual Wealth Protection Seminar: “How a Lawyer Can Protect a Client’s Wealth” Mark your calendars for this exciting event in Miami, Florida. Speakers include Jonathan Alper, Esq. on Where Does Florida Law Stand on Fraudulent Transfers” Mitchell Fuerst, Esq. on Introduction to Professional Privilege in Wealth Protection Cases – Civil v Criminal; Tax v Non-Tax; When to Claim the Fifth; How to Do it Right. Michael Markham, Esq. on Recent Asset Protection Case Decisions, Legislation, and Their Importance in Protection Planning Denis Kleinfeld, Esq. on Where to Situs a Trust – An Analysis of U.S. Asset Protection States and Alan Gassman, Esq. on Using Estate Planning Techniques to Optimize Family Wealth Preservation. For more information please email agassman@gassmanpa.com

WEBINARS:

THURSDAY, MARCH 28, 2013, 4:00 – 4:50 pm.

Please join us for the 444 Show – a monthly CLE webinar sponsored by the Clearwater Bar Association and moderated by Alan S. Gassman. This month’s topic is Divorce Law 101 for Lawyers and CPAs with Ky Koch, Mike Lewis and Judge Muscarella. To register for the webinar please visit www.clearwaterbar.org or email Janine@gassmanpa.com

MONDAY, APRIL 1, 2013, 12:30 – 1:00 p.m.

On the first Monday of each month the Clearwater Bar Association presents Lunch Talk. A free monthly webinar series moderated by Alan S. Gassman. This month’s speaker is Linda Chamberlain speaking on How to Write a Contract to Preserve Family Relationships When One or More Family Members are Paid for Caring for Mom and Dad. To register for the webinar please visit www.clearwaterbar.org or email Janine@gassmanpa.com

Alan S. Gassman, J.D., LL.M. is a practicing lawyer and author based in Clearwater, Florida. Mr. Gassman is the founder of the firm Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A., which focuses on the representation of physicians, high net worth individuals, and business owners in estate planning, taxation, and business and personal matters. He is the lead author on Bloomberg BNA’s Estate Tax Planning and 2011 and 2012, Creditor Protection for Florida Physicians, Gassman & Markham on Florida and Federal Asset Protection Law, A Practical Guide to Kickback and Self-Referral Laws for Florida Physicians, The Florida Physician Advertising Handbook and The Florida Guide to Prescription, Controlled Substance and Pain Medicine Laws, among others. Mr. Gassman is a frequent speaker for continuing education programs, publishes regularly for Bloomberg BNA Tax & Accounting, Estates and Trusts Magazine, Estate Planning Magazine and Leimberg Estate Planning Network (LISI). He holds a law degree and a Masters of Law degree (LL.M.) in Taxation from the University of Florida, and a business degree from Rollins College. Mr. Gassman is board certified by the Florida Bar Association in Estate Planning and Trust Law, and has the Accredited Estate Planner designation for the National Association of Estate Planners & Councils. Mr. Gassman’s email is Agassman@gassmanpa.com.

Thomas J. Ellwanger, J.D., is a lawyer practicing at the Clearwater, Florida firm of Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A. Mr. Ellwanger received his B.A. in 1970 from Northwestern University and his J.D. with honors in 1974 from the University of Florida College of Law. His practice areas include estate planning, trust and estate administration, personal tax planning and charitable tax planning. Mr. Ellwanger is a Fellow of the American College of Trusts and Estates Counsel (ACTEC). His email address is tom@gassmanpa.com.

Christopher Denicolo, J.D., LL.M. is a partner at the Clearwater, Florida law firm of Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A., where he practices in the areas of estate tax and trust planning, taxation, physician representation, and corporate and business law. He has co-authored several handbooks that have been featured in Bloomberg BNA Tax & Accounting, Steve Leimberg’s Estate Planning and Asset Protection Planning Newsletters, and the Florida Bar Journal. He is also the author of the Federal Income Taxation of the Business Entity Chapter of the Florida Bar’s Florida Small Business Practice, Seventh Edition. Mr. Denicolo received his B.A. and B.S. degrees from Florida State University, his J.D. from Stetson University College of Law, and his LL.M. (Estate Planning) from the University of Miami. His email address is Christopher@gassmanpa.com.